The war band we call the Vandals had crossed the Rhine in 406, far from Rome, when Honorius’s and Stilicho’s attention was focused elsewhere. They appeared in Africa more than twenty years later, under disputed circumstances. At a minimum, we must account for the romanization of a generation that elapsed between the crossing of the Rhine and the crossing of the Strait of Gibraltar. The young men who fought in Africa had all been raised to manhood inside Roman boundaries, and however romanized they were as its neighbors, they were assuredly more so now. Their role in Africa, moreover, was not that of men from the moon, but that of participants in local political dramas.

It was said, very likely falsely but said nonetheless, that they had been invited into Africa by one of the Roman generals there, seeking allies against rivals. In the course of a decade, they supplanted those generals and constituted the sole military power between Gibraltar and Cyrene. Carthage fell to them, less by main force than as a result of their growing rootedness in Africa itself. The advantage shared by all these rogue war bands—the ones we call barbarian—was their willingness to settle down and make a place their own. Rome had flourished by building professional, rootless armies that could go anywhere. Armies like that make excellent attacking machines, but if the task is defense, troops close to their homes have a great advantage: short supply lines, easy recruitment of replacements, and a passionate commitment to what they fight for. Roman government in Africa in the fifth century was a plant that lost its roots and so consequently lost its branches and flowers.

From an African point

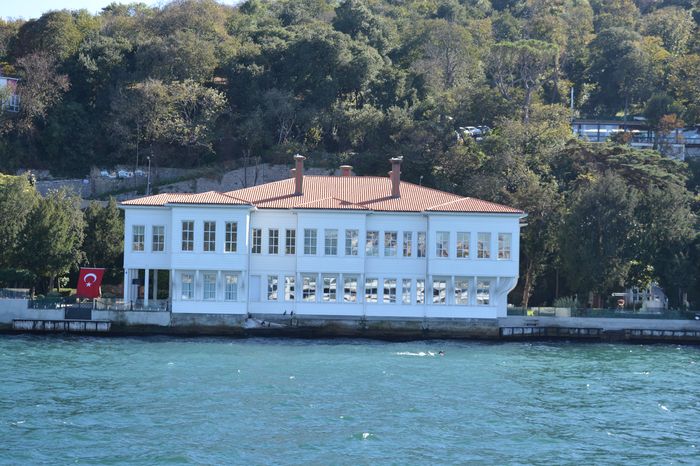

The new regime in Carthage owed nothing to anyone and saw no reason to regret its independence. From an African point of view, the heavy taxation that had drawn the produce of Africa, and much of its wealth, across the water to Italy could be done without very easily. The harbor of Carthage was renovated in the fifth century and trade clearly continued, though on terms more advantageous to the Africans than in the days of Roman taxes. Scholars continue to explore just how far the economic relations between Africa and the rest of the world were different in the last years of the fifth century from what they had been a century earlier, but the volume certainly subsided istanbul tours guide.

In Carthage itself, you might not notice the change. The Vandals, if we have to call them that, are famous for the decadent luxury of members of their upper classes, who clearly prospered well in their capital city. If archaeology were freer to pursue its business in Algeria than has been the case since before the war of independence half a century ago, we would know better just how much the decline of involuntary trade was reflected in the fading of prosperity in the Numidian uplands and the valleys where Augustine had grown up and lived. But the Vandals ran their province much as it had been run before. For the rest of the Roman world, the experience was a bit like the “oil shock” of 1973. Prices went up, and the sellers did just fine, while customers learned to make do with less for their money. The real blow of the Vandal conquest, in other words, was felt outside Africa.

Carthage was still Carthage. We have remarkable works of literature written there under Vandal rule, none more remarkable than Martianus Capella’s Wedding of Philology and Mercury, nine books in which old myth and new erudition dance together in what amounts to a handbook of the liberal arts for the most refined of literary tastes. The collection called Anthologia Latina, which we have in an eighth-century manuscript, was put together in Carthage c. 532-534: that is, just on the brink of the moment when Justinian’s forces would shatter a very civilized regime. Its riddles, epigrams, and showpiece verses that can be read backward and forward reflect a highly sophisticated audience, and the Vergilian centos they contain—that is, fresh poems made entirely out of lines of Vergil— required a well-educated audience to be appreciated at all The skirmishes at the beginning of Khusro’s reign.

Theoderic’s contemporary

Thrasamund, Theoderic’s contemporary on the throne of Carthage, appears as a benevolent monarch building and restoring the glories of his realm, as any Roman might. Latin was the only language in use, and when the Vandals were overthrown and we come to a period where more documentation and narrative survive, the life of a traditional Roman province was so easily resumed that we have to believe it was never really interrupted. Fulgentius, a writer both traditional (in his Mythologies) and orthodox (for his books of Christian theology), came from a family that had recovered its ancestral estates, where he spent his early years managing the business. (We met him on a pilgrimage to Rome when Theoderic was there.) If we did not know the story of Africa and its conquests, the archaeological remains we can see would not encourage us to think of great disruptions.