Fausta assured him

“This will be ours one day,” Fausta assured him, running her finger across the marble boundaries of nations and seas. “The whole of it,...

Britain and the channel

“Why not go beyond it?” Constantine bent over the map that occupied the top of the table. “Just north of a line drawn eastward...

Far north of the Antonine Wall

Constantine, however, spoke before his father could answer. “I still say I must earn whatever honor shall come to me,” he insisted. “Name me...

Roman rule had brought to Britain

Scrupulously treating the giant Bonar with the respect due a local king, he had taken him on a tour of the countryside, letting him...

Italians living in Ravenna

Totila, indeed, was willing enough to meet him before his city walls, but could not catch him there, since like the rest of the...

Word of honor to Photius

Now everybody took it for granted that Belisarius had arranged this with his wife and made the agreement about the expedition with the Emperor,...

Thirty gold centenaries

Quadratus, however, approached only to hand him a letter from the Queen. And thus the letter read: “You know, Sir, your offense against us....

Caucasus to menace the fertile plains

Brought up as a Roman, Tiridates had returned to Armenia after a victorious campaign against the Persians and had proved a very popular and...

The Emperors face softened

“The message said you wanted to see me at once.”

“Good! I’m glad to find somebody who obeys my orders.” The Emperor’s face softened. “It...

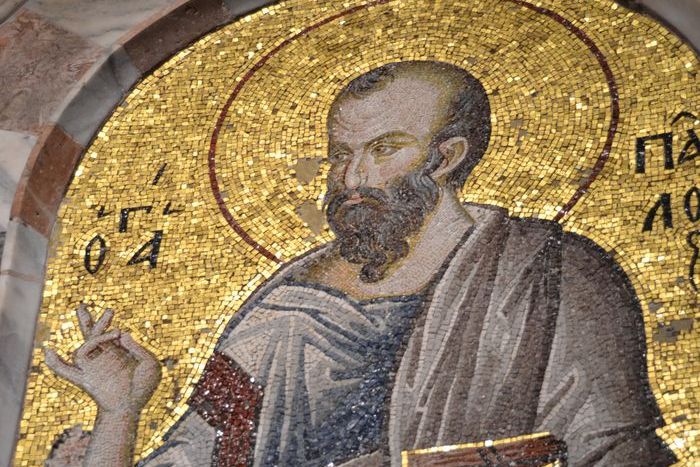

Flavius Valerius Constantinus at the age of twenty two

Thus at the age of twenty two, Flavius Valerius Constantinus was not only a father, an eventuality he had been quite too busy during...