The skirmishes at the beginning of Khusro’s reign concluded with what both sides called the “endless peace” of 532, purchased by Justinian for a mere 11,000 pounds of gold. “Endless peace” lasted eight years.

But when Justinian started sending his main forces west to fight even more foolish battles, Khusro doubtless understood what it meant and so in the late 530 s began pressing for tribute. There was an old argument that Persia deserved Roman support for what it did in protecting the Caucasus passes against invaders from the steppes, protection from which both Rome and Persia benefited. Rome never acquiesced, so the Persians took to the field. (They may have been encouraged by an embassy sent to Persia from Witigis, whom we shall see leading the beleaguered forces Justinian was trying to overthrow in Italy, now encouraging the Persians to open a second front.) City by city, Khusro got what he wanted, from Edessa, Hierapolis, and Apamea. In the year 540, he got as far as Antioch, raiding, plundering, and devastating the great city of the Roman east, which would never be the same. It could not have helped if the city’s residents heard that when Khusro returned to Ctesiphon, he built (or perhaps merely renamed) a city there “Khusro’s City Better than Antioch” to mock them!

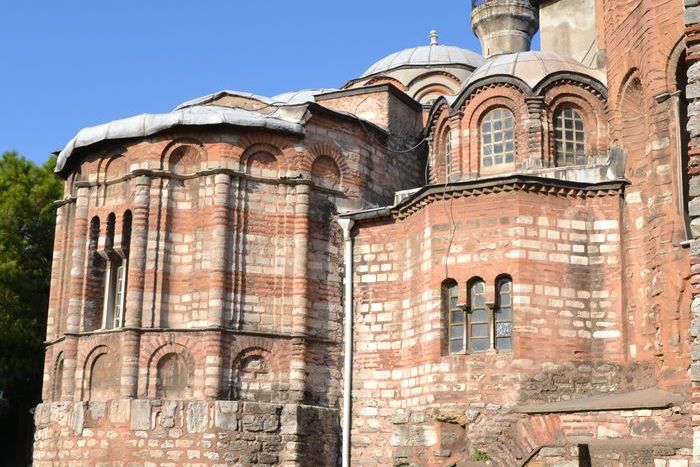

A revival of Roman attention in the early 540s led to a truce in 545, which would last, in the main, until Justin II frivolously returned to warmongering in the 570s, leading to another twenty years of intermittent conflict, and then again to twenty more years in the early seventh century. Because Procopius gives us a detailed account of the skirmishes of the late 520s and again some coverage of the 540s, it is customary to take these hostilities more seriously than they deserve to be taken in themselves, as though they represented (as Justinian probably thought they did) a recrudescence of ancient hostility between east and west, between great personified empires. No such backsliding needed to occur istanbul day tours.

At the end of the sixth century, the border between Rome and Persia would still be more or less what it had been 200 years earlier. Blood and treasure had accomplished nothing except the exacerbation of hostility and an impediment to mutual understanding. The stage was set for bloody and desperately ill-advised conflict in the seventh century.

SHOCK AND AWE IN AFRICA

The flotilla that Belisarius led to Africa was arguably the largest force of sea power ever assembled to that date, unless we believe that the emperor Leo’s ill-fated assault on the Vandals in 468 had numbered the 100,000 troops our sources imagine. Nothing like Belisarius’s flotilla would sail in the Mediterranean until the wars of Turks, Venetians, and Spaniards in early modern times. Ten thousand infantry, 5,000 cavalry, and another 1,000 light-armed mercenaries from amid the Huns and Heruls filled 500 carrier ships, accompanied by another 100 or so light warships for defense and maneuvering.

From Constantinople down through the Aegean

Setting out from Constantinople in June 533, with the prayers of the patriarch filling its sails, the flotilla made its leviathan way from Constantinople down through the Aegean with halts and delays, including one for a bout of dysentery among the troops. It passed Crete, then accepted the hospitality of Theoderic’s successors, who let its ships port and water in Sicily. From there it struck out bravely at just the right season for the African coast at the shortest crossing, heading for the Tunisian coast south of Carthage The reputation of Vandal Carthage.

The flotilla’s size was both its strength and its weakness. Laden with soldiers, drawn mainly from Balkan provinces that could ill afford to spare them, it probably carried enough weapons and food to sustain the trip on limited rations, but fresh water was a trickier business, as always with the transport of human beings on a salt sea, whether it was crack Roman legions or African slaves more than a millennium later. If rainwater failed to supply enough, the ships had to land periodically, with consequent devastation to all those on shore wretched enough to come within reach of hungry, thirsty, libidinous soldiers.

The Africa the flotilla approached was far from ready for it and easy to misread. Justinian was sure, Procopius was sure, and therefore every modern reader is sure that his troops were invading the “Vandal kingdom of North Africa,” which sounds like a very different thing from the Roman Africa that had gone before. As everywhere and every when in this period, it’s important to catch both the continuities and the discontinuities, region by region and place by place, to make sure we don’t deceive ourselves.